Identifying Chinese Swords by Andy Johnston

Copyright: public domain, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Editor’s Introduction

Once again, I am honoured and privileged to host another article by an esteemed collector. This time, our subject is the Chinese sword.

The dao and the jian are historical weapons steeped in heritage and cultural significance, serving as steely testaments to an interplay between war-fighting, artistic expression, and national identity. Characterised by certain features, these swords became symbols of tradition and the enduring legacy of China’s martial attributes. Rooted in centuries of evolution, both weapons witnessed the rise and fall of dynasties. This article, written by one of my favourite people, researcher and collector Andy Johnston, seeks to help readers quickly identify and better understand the jian and the dao, and I feel it does that with excellence. I hope you enjoy it as much as I did. If you would like to be a guest writer and contribute your own expertise to the website please get in touch.

Matthew Forde

Identifying Chinese Swords by Andy Johnston

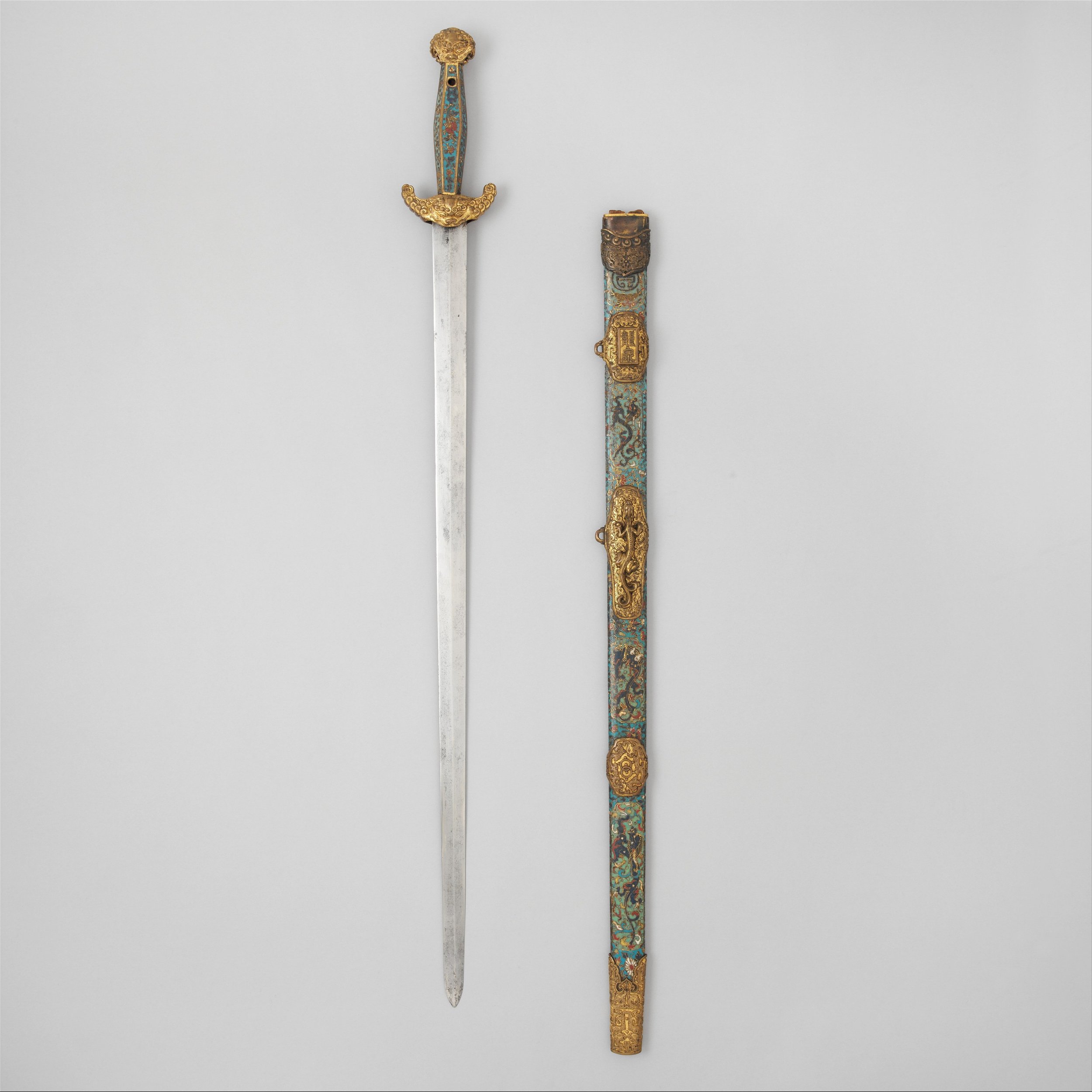

Ornate 17th century Jian with Lion face guard. Copyright: public domain, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Among Western arms collectors, it is very common to need assistance verifying and identifying various types of Chinese bladed weapons. This is a complicated prospect for several reasons. Firstly, China has a long history across a huge cultural landscape going back more than 2,000 years, across dozens of dynasties often with specific sub-cultural arms within its borders at any given point in history. Secondly, while it is always difficult to unify historical terminology for the weapons from centuries past, in many cases there is particular inconsistency in the terms used for Chinese arms across the centuries and disagreement among modern collectors which leads to confusion when discussing the history and development of a particular sword. Lastly, a problem that is not unique to China but has certainly become much more aggravated in recent decades, is the issue of counterfeit and fake items being artificially aged and presented to appear as genuine antique arms.

Sometimes this ‘mis-classification’ is honest (it is highly desirable to own a much older Ming saber, than a much more common later period Qing saber) but all too common as the epicenter of modern sword production, which takes place in southern China near the historic sword center of Longquan, gives counterfeiters easy access to modern blades which can then be weathered and sold for a considerable mark-up to the unsuspecting collector.

This article will serve to go over some of the most common types of Chinese sword-shapes seen in the collecting world today and, while not exhaustive, it will assist in preventing succumbing to some of the pitfalls that occur when reviewing potential Chinese antiques.

Note about sword terminology: as mentioned previously there is often disagreement between collectors, with complete accord for some names, and multiple names for other swords, and even divides between Western and Chinese collectors. For the majority of this discussion, I will be borrowing from the typologies of Peter Dekker from Mandarin Mansion who has done extensive research attempting to classify the weapons of Ming and Qing China.

The Jian

This section covers straight, double-edged swords. In use since the Bronze Age, originally as a battlefield sidearm, during the mid-Han Dynasty these weapons were eventually largely replaced by the dao for massed soldiers. While they were still seen on the battlefield in later dynasties, they usually appeared in small numbers and would be seen in the hands of higher ranking individuals such as commanders, generals, et cetera. A popular civilian weapon, during Ming and Qing China this was considered the ‘scholar’s sword’: the weapon of the literati and it had a strong cultural association with the Han Chinese. Jians typically have relatively small handguards and, despite being single-handed weapons, they have relatively long hilts to balance their swordplay. Larger two-handed versions did exist but those are now very uncommon.

The Civilian Jian

Jian are characterized by having a fairly uniform width for the length of their blades, with tips that range from spear-points to rounded ‘duck tongue’ styles. Ming and Qing period jians often have flattened diamond cross-sections, while fullers are rare until the turn of the 19th century. The majority of antiques are from the late Qing and are civilian examples. Blades are usually between 70cm and 75cm.

The Tuanlian Jian (The Militia Sword)

Found in village arsenals, these were supplied when it could not be assured that the state military could not protect the locals in times of lawlessness. Since these were being supplied by the scholarly gentry, the jian was supplied instead of the military dao. These jians tend to be much more crudely made than the gentlemanly version of the sword, being simple mass produced types for simple fighting needs.

The Shuangshoujian Jian (The Paired Sword)

Throughout the Ming and into the Qing jians are shown to be used occasionally in a paired format. During the mid-to-late Qing we see evidence of purpose-built sets of swords which slot together and fit into a single scabbard.

The Duan Jian (The Short Sword)

Popular in the late Qing period, especially with roaming sell-swords and musicians who traveled from town to town, these short swords began to be purchased as convenient souvenirs by 19th century Europeans due to their compact size, and so they are highly represented on the antique market. However, this demand from foreign markets caused ‘tourist’ versions to be produced alongside the actual functional swords in period.

The Beidou (The Seven Stars)

This is not a distinct type of sword but rather a recurring motif seen on the blades. Dating back to the medieval period, the seven brass points fixed onto certain swords represent the seven stars of the constellation Ursa Major (or, the Big Dipper). This is seen as the throne of Shàngdì (上帝), the ‘Supreme Deity’ in the ancient Chinese religion from the Shang Dynasty and it becomes important in Daoist rituals related to life and death.

A military peidao of the 17th century, as would be typical of the late Ming through to the mid-Qing Dynasties. Copyright: public domain, Metropolitan Museum of Art, AN 14.48.2ab.

The Dao

The dao character is used for Chinese sabers. However, unlike the jian which is relegated to sword-shaped weapons, ‘dao’ is a much more broad term, and it can refer to nearly any sized blade as long as it is single-edged—from a simple utility knife to long, glaive-like pole-arms. This article will initially review the common types of sword-sized dao.

Most daos are characterized by having modest blade-curvature, a round disc-style guard, and they are a medium to short length, as one-handed swords go. Two-handed varieties of dao were produced but these are less common.

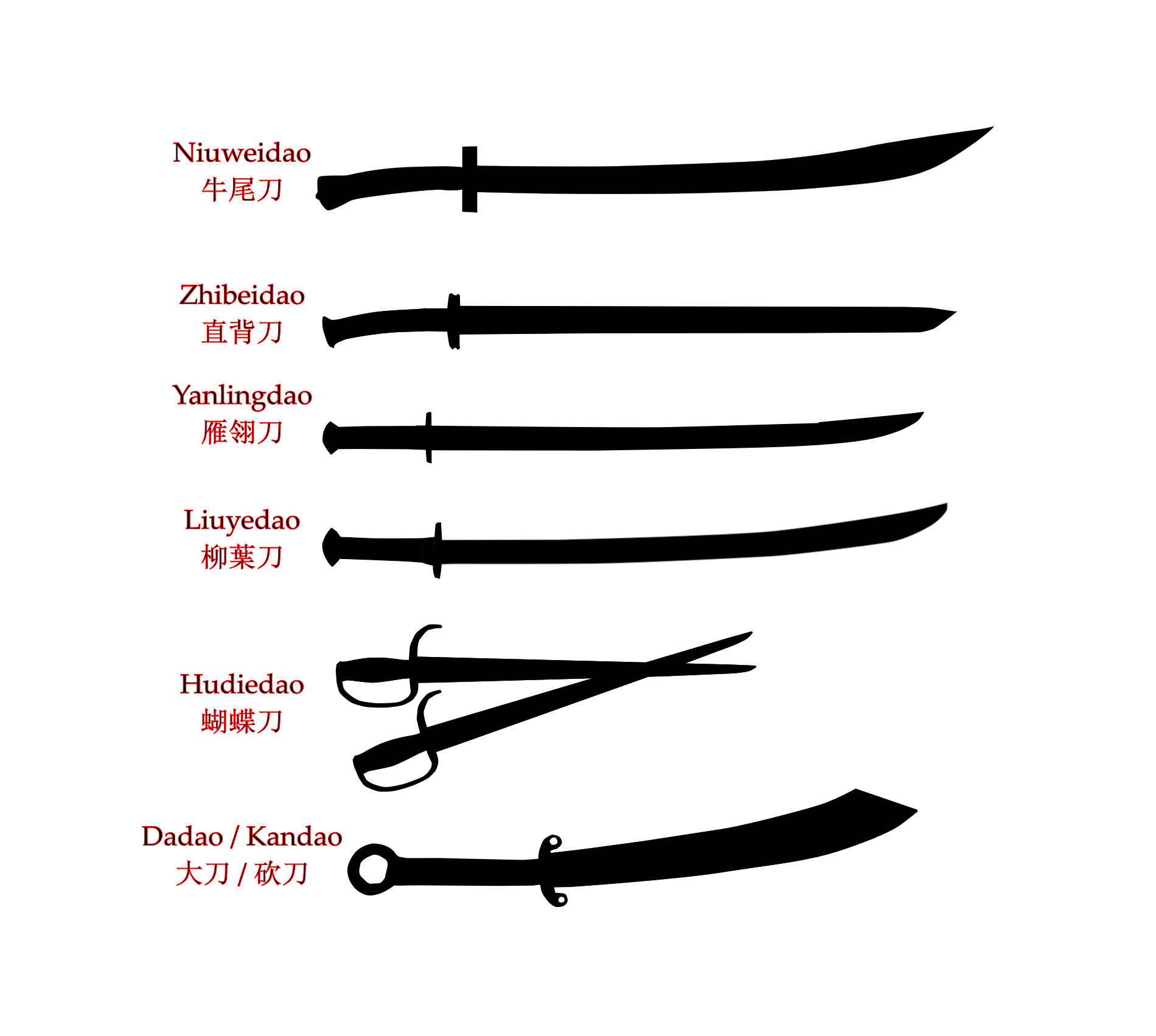

The Nieweidao (The Oxtail Saber)

By far the most commonly seen saber in the collecting world is the oxtail dao. Also called the ‘Chinese broadsword’, this is not an old design, likely dating to the mid-19th century. It became a popular civilian sword in a time when China experienced a great deal of lawlessness, warlords, and banditry. Rather than adhering to single design, like a military sword, there are many types of swords which have the flaring end of the ‘ox tail’, from fighting knife-sized weapons, to this blade type even appearing on pole-arms. The most typical blade length is something between 60cm and 80cm. These swords continued to be produced into the Republic Period, however, due to their popularity in martial arts schools, the wushu variants seen after the 1930s very rarely have fighting blades, and instead are just for demonstrations in the town square, or other wushu performances.

The Peidao or Yaodao (The Waist Saber)

Both of these words simply mean ‘waist’ saber and they are general terms to discuss military sabers worn at the hip. A variety of different blade designs were used for these peidao, and most of these have been named by collectors rather than distinguished as specific types of models during the period they were in use.

The Zhibeidao (Straight-Backed Saber)

Uncommonly seen. These are essentially back-swords with a straight spine, single-edged blade and, typically, a hatchet tip. This follows a very old blade design and remained in use with certain ethnic groups for a long time. This general shape continued to be used in areas such as Tibet.

The Yanlingdao or Yanmaodao (The Goose Wing or Goose Quill Saber)

More common in the Ming and early Qing eras, these were less common by the time of the 18th century. This type of dao starts straight and only shows a modest curve towards the end of the blade. In many cases these dao will have a simple tip or a small clip-back to aid with thrusting but a wide variety of tips and sub-types exist. This was the standard and most common type of military sidearm for much of the Ming and into the Qing.

The Liuyedao (The Willow Leaf Saber)

Perhaps the most common antique military dao, this blade-style eventually replaced the earlier curvature of the yanlingdao and features a gentle curve across its entire belly. Because the curve can be very slight it is not uncommon for a given sword to be difficult to easily classify as either a yanlingdao or a leiyuedao. As with the yanlingdao, the standard tip is either a simple point, or a clip-back but many variations exist for this curve as well.

An example of an extravagant Qing-era wodao with a Japanese-made blade. Copyright: public domain, Metropolitan Museum of Art, AN 32.75.301ab.

The Wodao or Qijadao (The Japanese or House of Qi Saber)

Less commonly encountered then the two prior military sabers, the name wodao translates as dwarf or bandit or Japanese saber after the attacks of the ‘woko’ Japanese pirates during the 14th to 16th centuries. Also called the ‘House of Qi’ dao in honor of General Qi Jiguang who battled these pirates, these peidao originally carried prized imported or captured Japanese blades shortened to fit Chinese hilts. During the Ming and into the Qing, local versions with variations of the general Japanese type were produced, leading to narrower yet thicker blades than typically seen on contemporary Chinese daos.

The Hudeidao and the Paidao (The Butterfly and the Shield Saber)

Paidao are a type of short sword, with knuckle-bows and a trapping quillon used in conjunction with the rattan shield known as a tengpai. These became popular during the 19th century as a village militia weapon, even as firearms became more common on the battlefield and heavier armor decreased, while smaller militias were less well equipped and still retained the use of shields. Coming in a wild variety of blade shapes, earlier forms tended to be long and more well designed for thrusting, while later designs show deeper blades that emphasized the cut.

A paired version called hudeidao or ‘butterfly knife’ was especially popular and can be distinguished by hilts which are flat on one side to accommodate both swords fitting into a single scabbard. These are well known in the martial arts community and modern display wushu versions greatly outnumber surviving Qing era antiques.

The Kandao and Dadao (The Chopping and Large Saber)

These were large types of ‘village cleavers’ with broad blades and they were popular in late 19th century China, featuring prominently among warlord enforcers as a show of power and means of capital punishment. These swords became famous during World War II by the use of ‘Big Sword Units’ in the Chinese National Revolutionary Army. Although eventually a military weapon, this did not have a pattern and tremendous variations abounded in both blade and hilt.

The Podao (The Rushing Saber)

This term covers a variety of polearm-sized blades, from medium to very long haft-length. During the Qing period, military regulations had more than six sub-types of podao with various ratios of blade-to-shaft length. Today, almost any type of Chinese glaive with a wide, flaring tip will be called a podao, regardless of how long the haft is.

The Guandao or Yanyuedao (Guan’s Saber or the Reclining Moon Saber)

A specific type of glaive which is characterized by its scalloped back edge, the ‘reclining moon dao’ is more commonly known as the ‘Guan dao’, named after the legendary figure Guan Yu from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. He is often depicted carrying this type of weapon despite it not being present during the Three Kingdoms period. These glaives are often more ornately decorated than the similar podao, commonly sporting intricate blade-collars or tunkou at the base of the guard, which can be in the shape of dragon’s heads.

If you would like to view more content from Andy Johnston you can find him discussing sword and sword-related research on Imgur and Reddit under the name Dlatrex. He even has an excellent T-shirt available to purchase. His YouTube channel is here.

Image Sources

All the images showing silhouettes are copyrighted to Andy Johnston and used with his kind permission. The remainder are in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons and Creative Commons, attribution:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%E6%98%8E%E4%BD%9A%E5%90%8D%E8%AE%BE%E8%89%B2%E7%BB%A2%E6%9C%AC%E4%BA%8C%E9%83%8E%E6%90%9C%E5%B1%B1%E5%9B%BE.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sword_with_Scabbard_MET_21123_-_cropped.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sword_(Peidao)_with_Scabbard_MET_268265.jpg

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a5/Sword_with_Scabbard_MET_DP119010.jpg

If this free article was useful then please consider supporting me on Patreon. By adding your support you gain access to a growing archive of useful articles, in-depth resources and advice, personal help with identifications and restorations, and, as I’m slowly liquidating my collection, early access to new sales. You can help out from as little as £1 (or $1) and everything genuinely helps. Thank you for your consideration and thank you for visiting.